Adobe Premiere Pro is loaded with so many outstanding features that it’s easy for a few to get lost in the mix. Even the most seasoned editor can discover seemingly hidden features in the software that could completely change the way they’ve done things for years. Myth #1: Loudness is Measured Using a Standard Called LKFS, LUFS and R128. Fact #1: LUFS and LKFS are reference units: R128 is a standard. As of this writing, the current loudness standards are based on a document called the ITU-R BS.1770-4 which is a recommendation by the International Telecommunications Union on the implementation of a series of algorithms that measure perceived loudness.

Myth #1: Loudness is Measured Using a Standard Called LKFS, LUFS and R128.

Fact #1: LUFS and LKFS are reference units: R128 is a standard.

As of this writing, the current loudness standards are based on a document called the ITU-R BS.1770-4 which is a recommendation by the International Telecommunications Union on the implementation of a series of algorithms that measure perceived loudness and true peak levels.

The title of the paper is literally “Algorithms to measure audio program loudness and true-peak audio level”.

The EBU R128 is a document (among several others) outlining the European response to that recommendation.

The ATSC A/85 in the US, and the TR-B32 in Japan are similar documents/standards and are all in close compliance with ITU-R BS.1770-4, with minor differences.

So, EBU R128 is not equivalent to LUFS or LKFS. It’s like saying decibels are the same as the manual explaining them.

LUFS and LKFS are a new reference unit of loudness measurement, but they are not the standard itself.

Myth #2: LU, LKFS & LUFS Measure Different Things.

FACT #2: LUFS and LKFS are terms which mean Loudness Units referenced to Digital Full Scale (dBFS) with K-weighting. (For more on K-weighting see Myth #4). As of 2016, LKFS and LUFS are exactly the same thing.

The Loudness Unit (LU) is equivalent to 1dB—that is, an increase (or decrease) of one LU is the same as raising or lowering by 1dB.

Here’s a bonus myth debunk: LU’s are NOT louder than dBs!

On an EBU R128 compliant loudness meter, a stereo -18dBFS sine tone at 1kHz measures -18 LUFS.

On an EBU R128 compliant loudness meter the scale can be absolute or relative meaning that on the meter itself you can set a specific target level to equal 0 LU or measure directly in LUFS.

On an “EBU Mode” loudness meter 0 LU = -23 LUFS (relative scale) or you can set it so that -23 dBFS/LUFS = -23 LUFS (absolute scale).

Here is a stereo -23 dBFS reference sine tone at 1kHz being measured by an EBU Mode meter on a relative scale reading -0.1 LU:

Here is the same stereo -23 dBFS reference sine tone at 1kHz being measured by an EBU Mode meter on an absolute scale reading -23.1 LUFS.

This is not as confusing as it first seems—on VU meters 0 can be calibrated to any desired reference level too, but typically 0VU is equal to +4dBu, which is equal to -20dBFS.

Myth #3: The new loudness standards are only for TV and post production.

Fact #3: Well, yes and no. It is true that the documents described above are primarily outlining broadcast standards (that’s what the “BS” in ITU-R BS.1770-4 refers to) but there is growing evidence that YouTube, iTunes and other major online music streamers are implementing some kind of loudness averaging.

They are not necessarily adhering to any of the broadcast standards though, YouTube seems to be normalizing audio on some official videos to between -14 and -12 LUFS...

... and iTunes’ “soundcheck “ feature appears to be leveling audio to around -16 LUFS.

Radio has yet to get on board with the standards, but when it does, the need for any musician, bedroom producer, mix engineer or mastering engineer to maximize loudness via brickwall limiting, or mix to arbitrary peak levels will come to an end. (See Myth #5 and Conclusion.)

Myth #4 Loudness Normalization will add more processing to my track and change it.

Fact #4: The loudness algorithms measure audio and adjust overall gain accordingly, they don’t process it.

Loudness Normalization uses EQ curves (designated K weighting) that closely resemble how the human ear perceives loudness, it then measures the average peak to trough difference of the entire “program material”, ignoring levels below a certain threshold, and then calculates a value called an integrated loudness level.

This Integrated level is then used to determine the overall loudness of the material and the levels of the whole program are turned up or down to comply with the various loudness standards mentioned above.

Furthermore, don’t confuse Loudness Normalization with Peak Normalization.

With Peak Normalization an audio file’s total gain is raised to specified amount (usually to 0 dBFS), but only based on the highest measured peak in the audio.

Here’s a plastic example; you have an audio file in which two characters are talking, and they are interrupted by loud gunshot. The gunshot nearly clips at -1 dBFS (i.e., the waveform nearly reaches 0dBFS) so peak normalizing the track will only raise the whole file by 1dB to 0dBFS, and leave the gain of the two characters talking perceptually unchanged — remember, raising gain by 1dB is barely perceptible to the human ear.

With loudness normalization the whole file is measured using the aforementioned set of algorithms and noise gates to determine the average or Integrated Loudness of the whole file. The algorithms and gates take into account the loud and quiet parts of the “program material” ignoring quiet parts (below a threshold of -70 LUFS as defined in the documents) and allowing for louder parts momentarily, and then spit out an Integrated Loudness value (I) after the whole file has been analyzed.

The Integrated Loudness level is the value that will determine the perceived loudness of the whole track.

When program material needs to be -23LUFs +/- 0.5 this is the value to check—it is important to understand that during playback parts of the material (music/dialog/EFX etc.) can be louder or softer than the target (I), but again, it’s the overall average loudness which is taken into account.

Referring to our plastic example above; as long as the gunshot peaks at or below a permitted momentary loudness level (EBU R128 specifies a maximum short term loudness (3 seconds or less) of +/- 5LU or -18LUFS) the whole file will be raised (or lowered) in volume “x” amount of LU so that the dialog (average loudness) sits at -23 LUFS while the gunshot (outside the average) has heaps of headroom to play into.

This will have more of an impact on the audience because the dialog is now audible and the gunshot has not been squashed down by a limiter or compression and thereby lessening the dynamics (and drama) between the two sonic elements.

The implications for more dynamics in music are also apparent.

Myth #5: dBFS peaks and RMS are more important to monitor than true peak or LUFS/LU readings.

Fact #5: Peak metering is rapidly becoming unnecessary, and essentially never gave us useful information to begin with. Intersample peaks are not correctly registered by peak-sample meters. For example, a traditional sample-peak meter that displays a max of -0.2 dB could read as high as +3 dB on a true-peak meter.

With the new Maximum True Peak Level of -1 dBTP, the previous PML (Permitted Maximum Level) -9 dBFS (as defined in ITU-R BS.645-2) is effectively obsolete and potentially replaces the previous music mixing standard for CD and online material of peaks no higher than -0.3 - 0.5 dBFS (once mastered).

As of this writing Logic X 10.2.2 has integrated True Peak measuring into all of its native meters and it is highly recommended to use true peak measurements from here on out.

As for RMS—RMS is much more useful for gauging the actual, longer term, levels of a given waveform, but RMS is only a measurement (or display) of signal voltage, so it doesn't really give us an idea of perceived loudness. Two music tracks measuring the same RMS values may not necessarily have the same perceived loudness because RMS does not take into account the psychoacoustic nature of apparent loudness as heard by the human ear, specifically that low, mid and high frequencies of the same level are not perceived as being the same loudness.

The Integrated loudness measurement specifically takes into account this aspect of human hearing perception of loudness and adjusts accordingly.

Conclusion

So what does all this mean for music?

In the EBU-R128 documentation it is explicitly suggested that no major changes to current mixing styles (as of 2016) are immediately necessary, but it is strongly recommended to consider the implications.

For music producers and engineers there are two choices:

- Mix as you always have, and have your music turned down later by loudness compliant playback systems

- Mix to the new loudness standard of -23 LUFS/-1 dBTP and utilize the large headroom and dynamic range it affords.

When you mix/master your music track to the current standard of 16 bit 44.1kHz with peaks at between -0.3 and -0.5 dBFS with an average RMS of say -12dB to - 6dB (brickwall limited and loud) this track when measured with a EBU compliant meter will show levels way above -23 LUFs (and possibly true peaks upwards of +3dB) and thus will be turned down until it has an integrated loudness of -23 LUFS.

No compression, no further processing, just literally turned down.

What this means is that pushing for high RMS values and squashing out dynamic range will now actually work against your music when your “sausage” is played against music mixed to utilize the dynamic range afforded by the -23 LUFS mix headroom.

“Loud” over compressed and brickwall limited music - read: music with no dynamics - really cannot compete sonically with more dynamic material in the new standards.

Related Videos

Last Updated on October 7, 2019

Have you ever been listening to music with your speakers turned up, only to have the next song be WAY too loud? Or watching videos online and jumped out of the chair as an advertisement blasted through your headphones after an online video? These happenings are caused by variances in loudness.

What Is Loudness?

Loudness is the perceived volume that a person experiences while hearing audio. Our perception of audio is based on a few different variables such as sound pressure, the tones or frequencies of the audio, and the duration of a sound or note. Another way to think about loudness is to imagine averaging the volume of loud and quiet parts instead of just focusing on the momentary decibel level.

Loudness is measured on a scale known as LUFS, or loudness units relative to full scale. One loudness unit (LU) is equal to one decibel since both metrics are based on the quantitative measure of sound pressure. The scale, ranging from quiet to loud, was created by assessing the physical and psychological characteristics of sound.

*LKFS is an older and commonly used name for LUFS and represents exactly the same loudness measurement.

Why Is There So Much Variance In Loudness?

When audio and video turned digital around the same time as the explosion of the internet, there were no rules or standards. People were creating and publishing content online at whatever volume they wanted, which created a very inconsistent experience for the viewer or listener.

Since humans often perceive louder music as better or preferable to softer versions, crafty professionals began to purposefully make their videos or music as loud as possible. This practice, known as the loudness war, led to even more volume differences and began to sometimes compromise quality when media was so loud that clipping or distortion occurred.

Fortunately, there are now more standards for loudness. TV broadcast stations have strict spec guidelines for video deliveries, which is why all the commercials you see on TV nowadays are the same loudness. YouTube applies its own loudness normalization to every video that gets uploaded. Music services like Spotify and Apple Music (if enabled) also normalize every song for a more consistent listening experience.

Loudness Standards

Loudness standards are primarily created by the ITU (International Telecommunications Union), which continually releases updated standards for audio levels. Many plugins and software include ITU recommendations as presets.

However, not all platforms have chosen to adopt the same ITU standard of loudness, which creates some wiggle room for how loud your audio should be. This means that the optimal loudness for a specific project usually depends on where the final product will end up being viewed. Luckily there are some standards and references that provide good guidelines if your project doesn’t have specs provided by a client or distributor.

- -23 LUFS –– Cinema / Films

- -16 LUFS –– Apple Music

- -14 LUFS –– Spotify

- -13 LUFS –– YouTube

Lowering the LUFS level creates more headroom and increases the dynamic range, but the sound quieter overall. Increasing the LUFS level decreases the dynamic range and usually means more compression, but the audio will be louder overall.

Measuring Loudness In Premiere

Most professional NLEs and DAWs come with ways to measure and adjust loudness within your active project. There are also many third-party plugins that are built specifically for loudness.

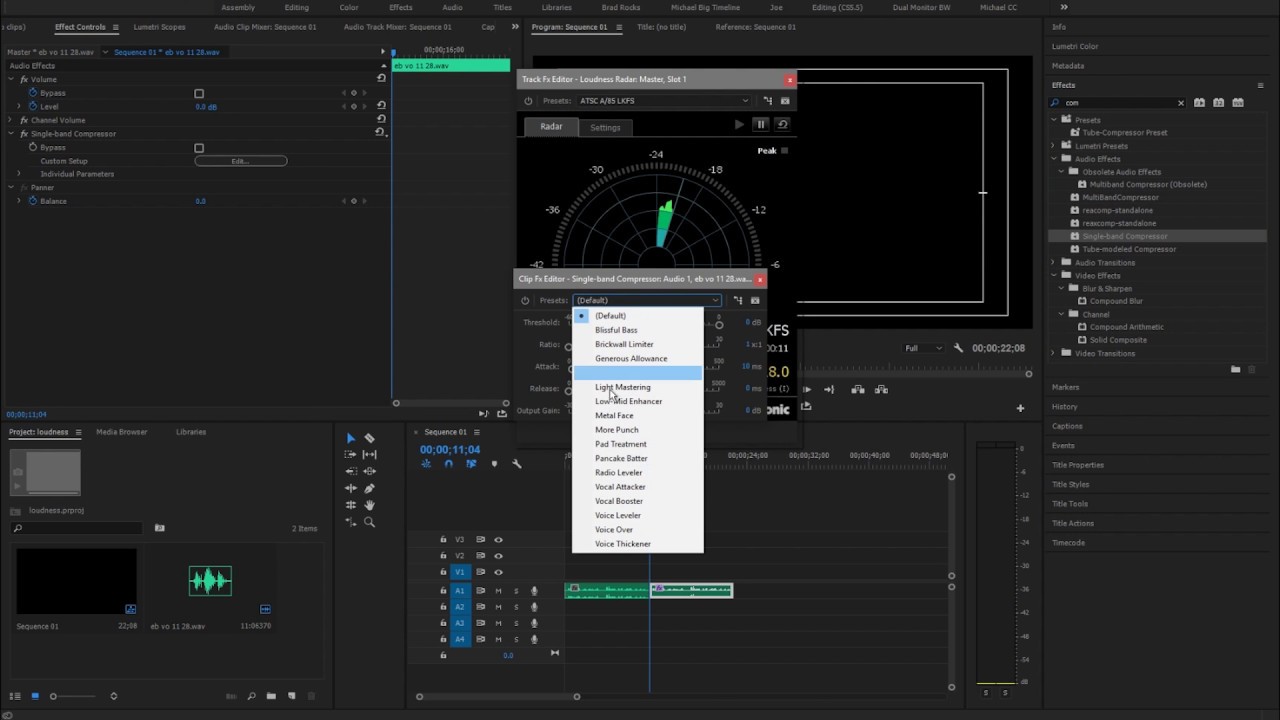

There are a few different areas within Premiere that are useful when dealing with loudness. A good place to start is the Loudness Radar plugin, which measures overall loudness for the duration of your project, along with other important factors such as peaks and momentary loudness.

- Apply the Loudness Radar to the master track in the audio track mixer.

- Double click the plugin to access its settings.

- Play your project from the beginning of the timeline.

- Watch how the Loudness Radar visualizes the average level of the audio over time.

- Note the program loudness (I) in the lower right corner. This number is the overall loudness.

- Click on Settings to configure more parameters, or cycle through the presets on the top bar.

The Loudness Radar plugin is passive, meaning it is providing metrics of the audio but doesn’t make any actual adjustments. Use the Loudness Radar as an insight into how loud your project is as a whole, as well as the variances in loudness between different aspects of the project.

For example, you might be working on a video that has different pieces of music in various sections. Analyzing each section with the Loudness Radar gives a visual guide to which areas are louder or softer relative to each other, allowing you to make informed adjustments to achieve a more desirable mix.

Adjusting Loudness In The Essential Sound Panel

The Essential Sound panel in Premiere is designed to be a user-friendly way to make many different audio adjustments. Follow these steps to adjust the loudness of individual sounds in your timeline, which is extremely useful for quickly leveling all dialogue, music, or sound effects.

- Open the Essential Sound panel in Premiere if it isn’t already visible (Window → Essential Sound).

- Select an audio clip (or clips) in your timeline that you want to adjust.

- In the Essential Sound panel, select the type of audio you are working on (Dialogue, Music, SFX, or Ambience).

- Click Loudness, and then click Auto-Match.

Premiere will then adjust the selected clips to its predetermined loudness standard for that particular type of audio. Keep your timeline organized and try adjusting the loudness for each separate audio type. The Essential Sound panel will target the following levels for each audio type:

- -23 LUFS –– Dialogue

- -25 LUFS –– Music

- -21 LUFS –– SFX

- -30 LUFS –– Ambience

Remember that the overall loudness will be higher when these elements play simultaneously.

Adjusting Loudness During Export In Premiere

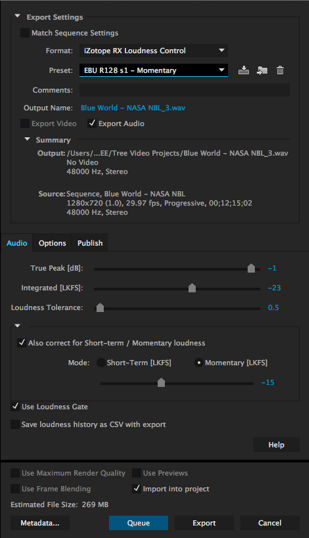

Premiere also allows you to adjust the overall loudness of your project in the export dialogue. Using this feature on your exports is the easiest way to keep your audio levels consistent. To set loudness before exporting, use these steps:

- Initiate the export window by clicking File → Export → Media or CMD+M on Mac.

- Click the Effects tab next to Video.

- Scroll down and enable Loudness Normalization

- Choose between different preset standards based on your delivery specifications.

- If you want to set your own loudness level, select the last preset: ITU BS.1770-3

- Edit the Target Loudness LUFS level.

Lkfs Premiere Pro After Effects

There are a few more configurable settings to consider, such as the Tolerance, Peak Level, and Peak Limiter. The default values for each generally provide good results, but you can hover over each parameter to learn more about what each option does.

Lkfs Premiere Pro 2020

If you find yourself usually aiming for the same overall loudness across all of your exports, try saving presets that include loudness settings in addition to your codec, resolution, and audio settings. This way, all versions of a particular project will have the same loudness, which provides a consistent viewing experience.